Game Changers

Golf, Healing, and Heroes: The Journey of Franko Poynter, a Vietnam Veteran and PGA HOPE Ambassador

By Jay Coffin

Published on

A two-hour conversation with Franko Poynter reveals so much about a man who has been through plenty in his 78 years.

And yet, he still has so much more to say.

After our interview, this writer awoke the next morning to a humble email sent from the soft-spoken Vietnam Veteran.

“I’m in no way anything special,” Poynter wrote. “I’m just a guy that took a different path in life to serve others. The true heroes are the amazing Veterans across our wonderful nation, and I’m blessed in some way to be a small part of their lives through PGA HOPE.”

Poynter is anything but ordinary, which is one of the many reasons why he represented the Indiana PGA Section in Washington, D.C., in October as one of 19 Ambassadors participating in PGA HOPE National Golf and Wellness Week. PGA HOPE (Helping Our Patriots Everywhere) is the flagship military program of the PGA of America REACH Foundation. It introduces and teaches golf to Veterans and Active Duty Military to enhance their physical, mental, social and emotional well-being.

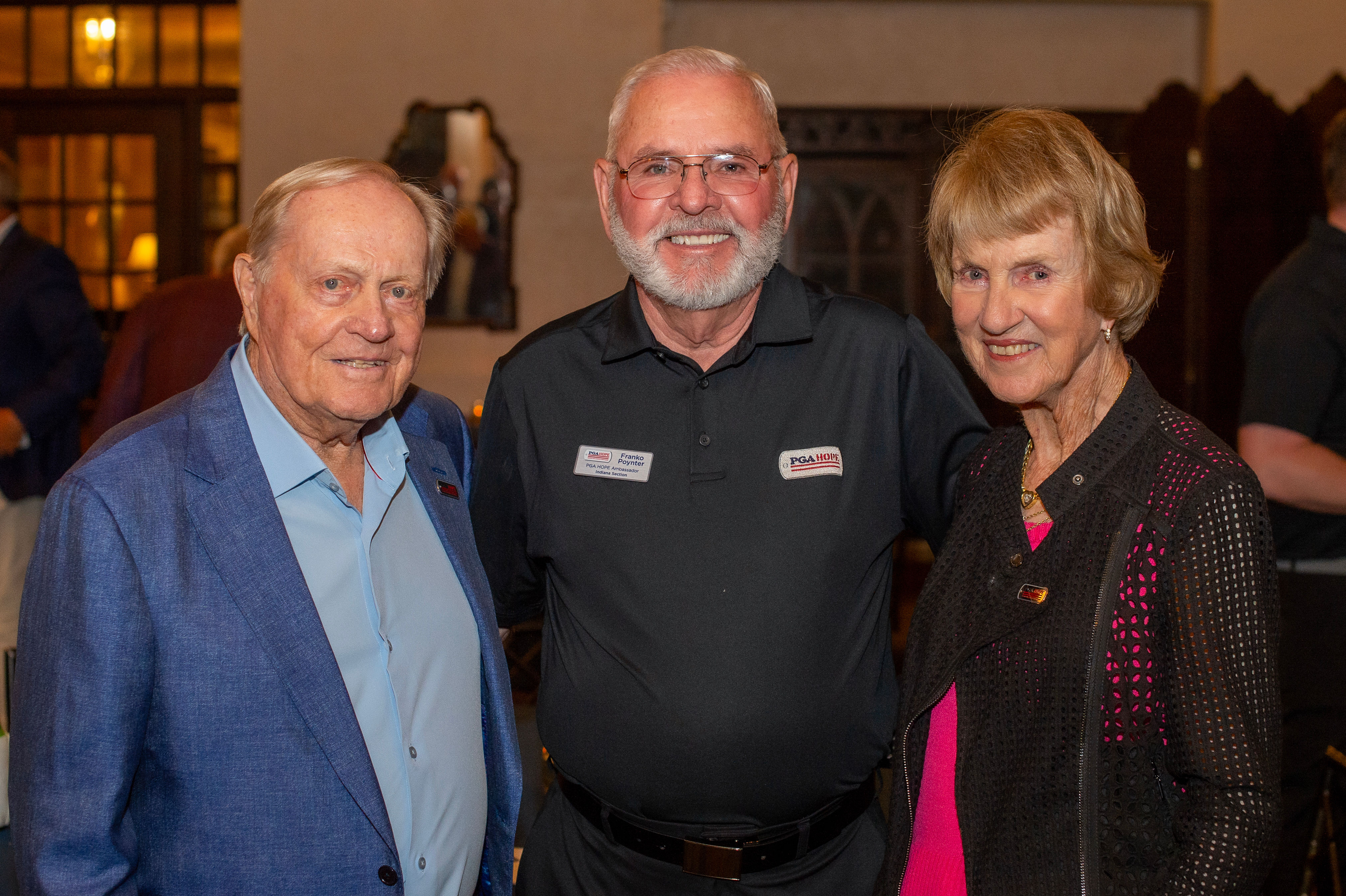

That week included time at Congressional Country Club, where the Ambassadors met Jack Nicklaus, who refereed a putting competition. It was especially meaningful to Poynter, who vividly recalls watching Nicklaus and Arnold Palmer on TV in the early 1960s while growing up in Lebanon, Indiana, 30 miles northwest of Indianapolis.

“It was a childhood dream come true,” Poynter said. “It was so impactful for me that I got to meet my real hero. He is the example that every professional athlete should be. Very few measure up to him. Meeting him was just amazing. Very emotional.”

Poynter himself is a real hero. He joined the Navy in 1964 at age 18 and three years later was serving on river boats in the Mekong Delta in south Vietnam. He admits that many of those he served with in 1967 and 1968 called him “old man.” He was part of the brown water Navy and served during the Tet Offensive, a surprise attack on Jan. 30, 1968, by the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army against the South Vietnamese Army and the U.S. military that lasted two months.

“No matter who was in that environment, you’re psychologically affected somehow,” Poynter said. “We had conflict in our own hearts. A lot of us were raised in a Christian environment, but everything we were taught was thrown out the window.

“The other part, for me, here I am a 21-year-old kid, still wet behind the ears and I’m responsible for others. It’s a burden no 21-year-old should ever have. Even now, it’s something that’s always on your mind.”

After returning to the U.S., Poynter still served in the Navy in California for three more years, and admits he was just going through the motions until his enlistment date arrived.

“My mom said, ‘I sent away my son, and I got back somebody I don’t know,’” he said.

During those three years, however, Poynter met a woman while back in Indiana on leave. They’d eventually get married and have two sons, William and Jeffrey, who were born at the end of his military career. That marriage ended after eight years and, according to Poynter, she remarried quickly and was awarded custody of the boys. Poynter struggled to see them until there was a confrontation with his ex-wife’s new husband, and suddenly he received custody of the boys, who he raised as a single parent for three years.

“I thought by being married that my life would assume some normalcy,” Poynter said. “I quickly discovered that wasn’t true.”

Poynter married again in 1980 and had daughter Ashley from that relationship, although she was born just as that marriage dissolved. His ex-wife fled Indiana with their newborn. Poynter bought a small farm in Belle Union, Indiana, and, after a few years, found the location of his daughter by chance. She was in Florida, and he attempted to have a relationship, but it wasn’t to be. (Unfortunately, that remains the case today, three decades later.)

“I never ever wanted my daughter to think that I didn’t value her,” he says sadly. “I never missed a child support payment. I increased it when I could.”

Poynter says that she’s been in prison on three different occasions and has long struggled with drug addiction. “That’s a burden I carry every day,” he said. “It weighs on you.”

Luckily, his relationship with his two boys, both now in their 50s, is healthier than ever. They live an hour away.

For most of the last 30 years, however, Poynter lived in Europe and South America – namely Brazil, Portugal, Mexico, Argentina, Panama, Bolivia, Paraguay and Uruguay. He completed mission trips in Europe. He assisted with a medical mission trip in the Amazon. He helped build homes in Mexico, where he is considered a permanent resident. To earn enough money to support his lifestyle, Poynter would return to Indiana a few months each year to flip houses and work on construction projects with companies that knew his reputation.

“I was resourceful,” he said.

During that time abroad, Poynter adopted a Hispanic daughter, Luz, who is now 46. In 2020, he married Estephanny, who has three children of her own. After returning to Indiana – now living in New Palestine – Poynter helps raise her two boys and a girl who are 8, 9 and 14.

“I’m telling you, I’m blessed beyond measure,” he said. “I get to be a real dad. It’s given me a chance to redeem myself in many ways.”

Two years ago, a Vietnam-era friend from the Marines invited Poynter to a PGA HOPE lesson at the Legends Golf Club in Franklin, Indiana. He was not interested. He was trying to stay isolated from the Veteran community. But after more prodding, Poynter relented and went to the session even though he didn’t own golf clubs. There, he met Crystal Morse, PGA head golf professional at Legends who ran the program. Fifteen minutes later, she had a full set of clubs for Poynter to keep. He was hooked.

“It was something I didn’t know I missed so much,” he said. “It was such a wonderful, calming experience for me.

“I can tell you, that day, when I got back into my truck, I lost it. I completely lost it. I could not shut the tears off. It overwhelmed me. As I was driving home, I was thinking, man, if this does this for me, I can’t imagine what it would do for all the Veterans who can be associated with it.”

Said Morse: “You run the program and you don’t realize that impact. I had no idea that he sat in his truck and cried. I had no idea. To hear that and how much it meant to Franko, the fact that we went through it together, that it’s impacting lives like that, it’s rewarding and I’m so thankful that we can provide a program like this that is so meaningful to so many.”

Two years after that initial session, Poynter was in Washington, D.C., representing his beloved Hoosier state as an Ambassador at PGA HOPE’s National Golf and Wellness Week. He was treated as if he was a member at Congressional, which is where he met Nicklaus in the putting competition. He returned home reinvigorated, with ideas about how he can help the Veterans in his area take advantage of the benefits of PGA HOPE.

Andrew Jent, the director of player development at the Indiana PGA, and Poynter have already discussed recruiting tactics. And just as importantly, they want to make sure they look after the alumni once they complete the program.

“The biggest thing I’ve seen with him is how outward he is with people,” Jent said. “At first, he was a little shy, but he always had a smile on his face. As I got to know him more, he’s now genuinely asking about me. How am I doing? What’s going on in your world? Trying to make the personal connection.

You run the program and you don’t realize that impact. I had no idea that he sat in his truck and cried. To hear that and how much it meant to Franko, the fact that we went through it together, it’s rewarding and I’m so thankful [for PGA HOPE].

Crystal Morse, PGA

“We want him to be the face of our graduate program. What are things that people are talking about that we’re missing? If they don’t feel comfortable coming to anyone else, they can go to Franko and talk about an idea.”

It’s a role that Poynter relishes and one he’s prepared to tackle, just as he has everything else in his life. He served in Vietnam, has been to places far and wide, has experiences that not many else have had. He’s even defeated bladder cancer, which has reoccurred several times over the years and has caused him to have six different operations.

“Some things still to this day don’t make sense,” he said. “If you’re in an experience and you have triggers, you can go back and think about something that’s as real today as it was 50 years ago. Because you’re experiencing the same emotions. All that drama that was in your life and how you sorted through it. I think a lot of vets, including myself, pretty soon you become callous to what’s around you. You withdraw back within yourself.

“I don’t want these younger guys to carry that dark shadow for all the years that I carried it. That’s what motivates me – not only my healing process, but to be a part of the healing process for somebody else.”

To support PGA HOPE and its mission to help Veterans thrive through the game of golf, visit pgahope.com today.