Game Changers

Against All Odds: Ryan Carr’s Journey from Fighter Pilot to PGA HOPE Ambassador

By Jay Coffin

Published on

When Ryan Carr was 5, he declared to anyone who would listen that he was going to become a fighter pilot.

Friends and family dismissed it.

“Do you know how many people are fighter pilots?” they told him. “It’s not going to happen.”

That only fueled him.

“I was like, guess what? I’m going to prove you wrong,” Carr said. “That was my whole goal growing up. A lot of what I did was focused on that: Hey, I have to figure out a way to put myself through college, I have to figure out how to do a lot of these things.”

Even if it took 20 years.

Carr grew up in Cumming, Georgia, just north of Atlanta with three siblings and a half-brother whom he met for the first time in high school. He played football, baseball and lacrosse, and he earned a black belt in karate by the time he was 8. After high school, he headed to one of the state’s premier institutions, Georgia Tech, before transferring to the University of Texas after a year.

That turned out to be a blessing.

Carr met his future wife, Elizabeth, on his third day on campus. They were in the same student group, she happened to live in the same apartment complex, and she brought him brownies as a welcome gift. The two stayed up talking until 3 a.m. Carr called his buddies the next day to tell them he had just met his future wife. They were engaged a year later.

Carr graduated with a degree in mathematics and a minor in Naval Sciences through the Navy ROTC program. He married Elizabeth a month later.

Here’s the wild thing about Carr’s goal – the first time he’d ever been on a commercial airplane was when he was 18. He flew in a fighter jet two years later in San Antonio.

“I had a miserable time, one of the worst times of my life,” Carr said. “I was sick the whole time.”

Two years after the nauseating ride, Carr went to Navy aviation pre-flight indoctrination (API) in Pensacola, Florida, hoping for the best. At this point, Carr was not only still determined to become a fighter pilot – he was obsessed with becoming the best.

He was a distinguished graduate for the initial part of flight school, tops in his class. Carr remained in Pensacola for the next stage, primary flight training, but it was halted for three months because of budget cuts. Rather than take time to relax, he built his own training syllabus to keep him on schedule, effectively learning everything he’d need to know before the classes even happened. Word of Carr’s syllabus moved up the ranks to a few admirals, and Carr received an award for his work, which quickly became the standard for future classes.

In November 2019, Carr finished top of his class again and got his ticket to the next stage, allowing him to move onto advanced flight training. He was the only person from his squadron given the assignment. He was one step closer to becoming a fighter pilot.

Carr moved to Kingsville, Texas, without Elizabeth, who initially stayed in Pensacola for another four months because she didn’t want to leave the students she was teaching. That made the phase more difficult. Carr was flying a T-45 Goshawk and learned how to dog fight, fly in formation and how to use bombs – all the tactical elements in the aircraft.

Again, he excelled. In April 2021, almost 20 years after telling his family and friends that he wanted to become a fighter pilot, Carr “winged.”

“They give you those wings of gold, you’re no longer a student aviator, you’re a Naval aviator,” he said. “You’re now a fighter pilot.”

The Carrs moved to Lemoore, California, where Ryan would go through SERE training (survival, evasion, resistance and escape). The 1,700-mile move happened so quickly that they had to live in a hotel room for a month before they could close on a house. Elizabeth was eight months pregnant with their first child.

“I’ve now showed up to the mecca,” he said. “I’m 25 years old, and I’m a fighter pilot, 20 years after I initially said that’s what I want to do, I reached it.”

Only in California for 10 days, Ryan awoke one morning to his wife having a seizure next to him in bed. Ryan called 911 and then stabilized Elizabeth and the baby. After being rushed to the hospital, Elizabeth gave birth to daughter Leighton in May 2021. Everyone was healthy, but Elizabeth doesn’t remember anything that happened, including the birth.

Two weeks later, Carr left for SERE training.

“They teach you how to be a POW and how to survive,” he said. “I’m literally sitting in a cement doghouse, getting pseudo-tortured while my wife is back home with amnesia trying to take care of a 2-week-old baby. I started beating myself up.”

Carr made it through initial FA-18 Super Hornet training and had designs on becoming a Top Gun pilot. But he never took care of himself mentally.

“This pressure to maintain all of this, to prove the haters wrong, all of a sudden toppled down,” he said. “I started noticing as I’m driving to work, driving down the highway west toward base from our home, thinking I don’t want to keep doing this. I had fleeting thoughts of wanting to go 80 miles an hour, unbuckle my seatbelt and drive my car into a tree.

“I thought it was me being weak. When I was at Georgia Tech, things were going wrong, I had the same thoughts: No, keep going, you’re just being weak.”

Carr told his leaders of his suicidal thoughts, and they urged him to take a break at Thanksgiving and come back refreshed. That didn’t work. Same thing during Christmas. Carr said he spoke to three different people about his mood during that stretch.

Eventually, in late January 2023, Carr saw a flight doctor and admitted that, the night before, he got in his car and started driving 60 miles toward Sequoia National Park with thoughts of freezing himself to death. Fortunately, as he was getting closer, he kept thinking of his daughter and turned around.

“I need help,” Carr told the physician. “I’ve thought about killing myself for weeks now.”

The waitlist for mental health help was six weeks. Carr was put on desk duty, arriving at 6 a.m. and leaving after the last flight ended at 10 p.m. Instead of flying, he was watching others fly, all while working grueling hours.

Carr needed an outlet, something that he could do to stay competitive with himself and try to get better every day. He turned to golf.

“I’m a sports nut, never played golf,” he said, “but I guess we’re going to try.”

That was 20 months ago.

In May 2023, he saw Jack Nicklaus in an advertisement on TV for the PGA HOPE program during the PGA Championship. PGA HOPE (Helping Our Patriots Everywhere) is the flagship military program of the PGA of America REACH Foundation. It introduces and teaches golf to Veterans and Active Duty Military to enhance their physical, mental, social and emotional well-being. Carr called around his area and couldn’t find an active program.

In late September, Carr was told he would be medically retired, and in four weeks he’d be officially done with the Navy. He wanted his kids – Elizabeth gave birth to son, Bennett, a few months earlier – to be closer to their grandparents, so the family moved to Acworth, Georgia.

“I never went on a full deployment, there’s a lot of stuff that I kick myself, because I didn’t do,” Carr said to sum up his military career. “But at the same time, I was able to accomplish my goals: I was able to be a fighter pilot, I shot missiles, I shot bombs, I flew upside down, I flew over the Pacific Ocean and over the Atlantic Ocean.

“That’s cool, but at the end of the day, my No. 1 achievement – I was sitting in group therapy and, all of a sudden, a sailor from my division came in. He said to me, ‘The only reason I’m here is, if you can do it, I can do it.’ That was probably the absolute biggest accomplishment of my military career. I was able to impact somebody enough that they were willing to also be big enough to ask for help.”

The end of Carr’s military career marked the beginning of his PGA HOPE journey with the Georgia PGA Section. As soon as he moved to Georgia, he went to an outing at Cobblestone Golf Course and met Carly Riordan, the foundation manager for the Georgia PGA Section. She noticed that Carr was much younger than most of the other veterans and was excited about all of his ideas. Riordan then introduced Carr to Robert Leahey, the Section’s PGA HOPE Ambassador from 2023.

“Ryan is like having another employee on my team,” Riordan said. “He goes above and beyond, works so hard. He will call me any time of day and always has some idea of some way we can be better. I know I can rely on him. But I also know that golf is truly saving his life.”

Said Leahey: “He’s a young guy, had a great story to tell, it was perfect timing getting him involved. We spoke about the challenges he faced. We talked about the challenges that I faced. We had similar issues in dealing with stressors. He’s a fantastic guy, he’s exactly what we needed. With him, everything is possible. We’re able to tackle a lot in Georgia and really get the word out.”

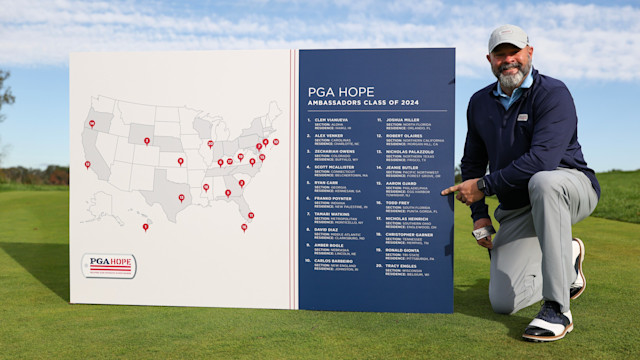

Carr, 29, represented the Georgia PGA Section in Washington, D.C., in October as one of 19 Ambassadors participating in PGA HOPE National Golf and Wellness Week, which included time at Congressional Country Club.

To say Carr is obsessed with the game is an understatement. He works for Georgia Tech as a defense contractor, which keeps him involved in the tactical side of the military while still spending time with his family and playing golf. He hits balls, or plays, nearly every day. His goal is to play 85 rounds this year. His handicap was 28 to start the year and is now down to 12.4. He wants to get it below a 5 by the end of 2025.

“Every day it’s, what can I do? What can I do to introduce golf to somebody or introduce the benefits of golf to somebody?” Carr said. “Golf has given me so many opportunities. I know that tomorrow is a new day and I’m always hopeful that it’ll be a good day.

“Golf is just the vehicle for what we can do to better our lives.”

To learn more and support PGA HOPE’s mission, visit pgahope.com.