NEWS

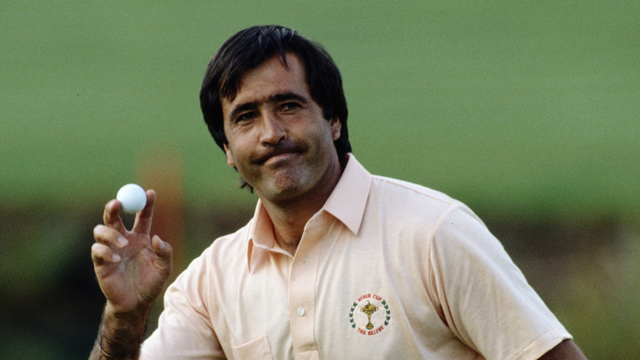

Ballesteros, 54, dies after courageous struggle with effects of brain tumor

MADRID, Spain -- Seve Ballesteros was a genius with a golf club in his hands, an inspiration to everyone who saw him create shots that didn’t seem possible. The Spaniard’s passion and pride revived European golf and made the Ryder Cup one of the game’s most compelling events.

Ballesteros, a five-time major champion whose incomparable imagination and fiery personality made him one of the most significant figures in modern golf, died Saturday from complications of a cancerous brain tumor. He was 54.

His career was defined not only by what he won, but how he won.

"He was the greatest show on earth,” Nick Faldo said.

Tiger Woods said on Twitter: “Seve was one of the most talented and excited golfers to ever play the game. His creativity and inventiveness on the golf course may never be surpassed. His death came much too soon.”

A statement on Ballesteros’ website early Saturday said he died peacefully at 2:10 a.m. local time, surrounded by his family at his home in Pedrena. It was in this small Spanish town where Ballesteros first wrapped his hands around a crude 3-iron and began inventing shots that he would display on some of golf’s grandest stages.

“I held his hands, caressed them and thought: ‘what these hands have done in the world’,” his brother Baldomero told Spanish agency Efe. “He knew he was dying, and he did it with full presence of mind.

“What is leaving us is more than a brother, a son or a father; what is leaving us is glory.”

Ballesteros won the Masters at 23, leading by 10 shots at one point in the final round. He was a three-time winner of the British Open, no moment greater than his 1984 victory at St. Andrews. He was as inspirational in Europe as Arnold Palmer was in America, a handsome figure who feared no shot and often played from where no golfer had ever been.

“Today, golf lost a great champion and a great friend. We also lost a great entertainer and ambassador for our sport,” Jack Nicklaus said. “No matter the golf that particular day, you always knew you were going to be entertained. Seve’s enthusiasm was just unmatched by anybody I think that ever played the game.”

In a long list of spectacular shots, perhaps the most memorable came from a parking lot next to the 16th fairway at Royal Lytham & St. Annes in the 1979 British Open. Leading by two in the final round, he drove his ball into the lot, had a car removed to get his free drop, then fired his second shot to 15 feet and made birdie on his way to his first major.

“He was a man who got into trouble. Only for Seve, there was no such thing as trouble,” Gary Player once said.

Headlines such as “The Inventor of Spanish Golf” and “Life of a Legend” were splashed across Spanish media as athletes and other notable figures from around the world paid tribute Saturday.

“This is such a very sad day for all who love golf,” European Tour Chief Executive George O’Grady said on the tour website. “Seve’s unique legacy must be the inspiration he has given to so many to watch, support and play golf, and finally to fight a cruel illness with equal flair, passion and fierce determination. We have all been so blessed to live in his era.”

Lee Westwood, the No. 1 player in the world, said on Twitter: “Seve made European golf what it is today.”

An emotional Jose Maria Olazabal played through tears at the Spanish Open on Saturday, overcome by grief.

Olazabal, who teamed with Ballesteros as the most successful pairing in Ryder Cup history, broke down as players honored Ballesteros with a minute’s silence.

“I just played the most difficult round of my life. It was very tough to make it to the first tee and hit the first drive,” said Olazabal, who shot a 3-over 75. “I don’t think there will ever be another player like him. There can be others that are very good, but none will have his charisma.”

Ballesteros’ last challenge came from an unbeatable foe: cancer.

He fainted in a Madrid airport while waiting to board a flight to Germany on Oct. 6, 2008, and was subsequently diagnosed with the brain tumor. He underwent four separate operations, including a 6 1/2-hour procedure to remove the tumor and reduce swelling around the brain. After leaving the hospital, his treatment continued with chemotherapy.

Ballesteros looked thin and pale while making several public appearances in 2009 after being given what he referred to as the “mulligan of my life.” But he rarely was seen in public after March 2010, when he fell off a golf cart and hit his head on the ground.

His few appearances or public statements were usually connected to his Seve Ballesteros Foundation to fight cancer. He wanted but was unable to take part in a champions exhibition at St. Andrews for the British Open.

Ballesteros won a record 50 times on the European tour, his first victory as a 19-year-old in the Dutch Open, his last when he was 38 at the Spanish Open in 1995. That also was his last year playing in the Ryder Cup, where he had a 20-12-5 (win, lost, drawn) record in eight appearances. Ballesteros was captain in 1997 when Europe won at Valderrama.

“He did for European golf what Tiger Woods did for worldwide golf,” three-time major champion Nick Price said from a Champions Tour event in Alabama. “His allegiance to the European Tour was admirable.”

Ballesteros was the reason the Ryder Cup was expanded in 1979 to include continental Europe, and it finally beat the United States in 1985 to begin more than two decades of dominance. While others have played in more matches and won more points, no player better represents the spirit and desire of Europe than Ballesteros.

His battle went beyond the golf course.

Ballesteros did not play in the 1981 Ryder Cup over a dispute with Europe over appearance money. He later battled former PGA Tour Commissioner Deane Beman over how many tournaments he was required to play.

He was feisty. He was proud. He was charming. He made people watch, and he usually gave them something to remember.

Ballesteros announced his retirement in a tearful news conference at Carnoustie before the 2007 British Open. He had returned to Augusta National that year to play the Masters one last time, but shot 86-80 to finish last. After turning 50, he tried one Champions Tour event, but again came in last.

His back was ailing, his eyes were less lively, his best game had left him years earlier.

“I don’t have the desire,” Ballesteros said at the time, though he remained active in golf even after he stopped playing regularly, mainly through course design.

His desire was as big a part of his game as any shot he manufactured from the trees, the sand -- just about anywhere on the course.

Born April 9, 1957, in Pedrena, Ballesteros first gained acclaim at 19 in the final round of the British Open at Royal Birkdale, where he threaded a shot through the bunkers and onto the green at the 18th hole, finishing second to Johnny Miller and in a tie with Nicklaus.

“He invented shots around the green,” Nicklaus said in the weeks before Ballesteros was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame in 1999. “You don’t find many big hitters like him with that kind of imagination and touch around the green.”

Ballesteros went on to win the Order of Merit on the European Tour that year, the first of six such titles. Two years later, he won the first time he teed it up in America, a one-shot victory at the Greater Greensboro Open.

His first major came a year later, at Royal Lytham in the 1979 British Open, where he made birdie from the parking lot.

“I won the Open … in a different way from most people that have won the Open,” Ballesteros once said. “I was right, left, in trouble most of the time. But I finished the hole quicker than the rest of the field. That was the name of the game.”

Partly because of his humble roots, partly because of his Spanish blood, Ballesteros always played as though he had something to prove. Even after some called him “Car Park Champion” for his shot at Lytham, the Spaniard showed that was no fluke when he arrived at Augusta National the next year.

He obliterated the field in the 1980 Masters, much like Woods did in 1997. Applying his genius to a course built for imagination, he became at 23 the youngest Masters champion until Woods won at age 21.

Ballesteros won the Masters again in 1983, and he was equally dominant in golf’s oldest championship. He won the British Open in 1984 at St. Andrews over Tom Watson, then at Lytham in 1988 by closing with a 65 to beat Price and Faldo.

Despite his five majors and 87 titles around the world, Ballesteros forever will be linked to the Ryder Cup. He developed an “us against them” attitude that became infectious with what had been an inferior European team. He made his teammates believe.

Ballesteros was headed for defeat in 1983 at PGA National, his ball beneath the lip of a bunker, some 245 yards from the green, when he lashed a 3-wood to the fringe and escaped with a halve against Fuzzy Zoeller. The Americans narrowly won, but the Ryder Cup was never the same after that year—and perhaps after that shot.

He teamed with Olazabal to become the most formidable partnership in Ryder Cup history, producing an 11-2-2 record. In his final Ryder Cup, at Oak Hill in 1995, he played Tom Lehman in singles and didn’t hit a single fairway on the front nine, yet was only 1 down. Lehman calls it the greatest nine holes he ever saw.

Ballesteros and his wife Carmen divorced in 2004. They had three children together.

The funeral will be Wednesday in Pedrena with family and intimate friends attending the subsequent wake. Three days of official mourning will be held in Cantabria, regional government head Miguel Angel Revilla announced.