NEWS

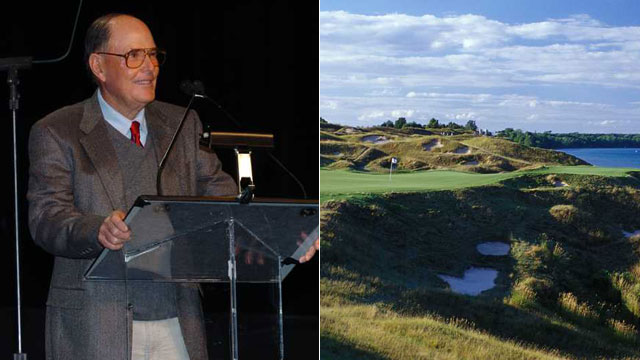

Whistling Straits designer Pete Dye, at age 89, remains true to his vision

By Gary D'Amato

Published on

Pete Dye doesn't own a cellphone. He doesn't own a computer. If you want to reach him you have to call him at home and hope to get lucky because, at 89, he's still traipsing all over the country, pushing dirt and building golf courses.

On a whim, you call on the Fourth of July. He picks up on the second ring.

How are you doing, Pete?

"Oh, I'm doin' pretty good," he says in his Midwest twang. "It's the Fourth of July, and I'm watching Lawrence Welk."

It's a safe bet that not too many people are watching Lawrence Welk on the Fourth of July. Then again, Paul "Pete" Dye is one of a kind.

The man who designed all four courses for Kohler Co., including Whistling Straits, site of the 97th PGA Championship (Aug. 13-16) has been called a genius and an artist. He is both of those things. He's also been called "the only architect who can outspend an unlimited budget." Yes, he may be that, too.

In so many ways, Dye is a throwback. A former insurance salesman, he had no formal training as a golf course architect and shuns 21st-century technology. He's more comfortable pushing dirt in a 'dozer or walking a routing in mud-splattered khakis than he is attending cocktail parties at course openings.

He has never drawn up fancy plans for a golf course, unless you count holes sketched on a napkin a fancy plan.

"Pete Dye designs everything from his vision – the vision of a visionary," says Herbert V. Kohler Jr., who hired Dye in the mid-1980s to build Blackwolf Run and kept rehiring him even though they fought, at times, like brothers.

"He walks the course," Kohler says. "He puts a dot for a tee, a dot for the landing area and a dot for his green and that's the last time pencil hits paper."

Or, as Dye explains the process, "I never have drawn plans. I go out there and I yell at (the shapers) and scream at them and talk to them. Most of 'em come out pretty good, I guess."

Pretty good? Ten of the top 100 courses in America, according to Golf Digest magazine's 2015-'16 ranking, are Dye designs. The Straits Course at Whistling Straits is No. 22 on the list and the River Course at Blackwolf Run is No. 91.

Dye also designed the Stadium Course at TPC Sawgrass, with its oft-imitated island green; the Ocean Course at Kiawah Island, S.C., where Rory McIlroy won the 2012 PGA Championship and the U.S. beat Europe in the famous "War by the Shore" Ryder Cup in 1991; and Crooked Stick in Carmel, Ind., which launched the phenomenon known as John Daly.

The skeleton of one of his earliest designs (with a young Jack Nicklaus) at the old Playboy Club in Lake Geneva is buried under a Bob Cupp redesign at what is now Grand Geneva Resort. Dye also designed Big Fish Golf Club in Hayward.

He was the PGA Distinguished Service Award winner in 2004 and is just one of five golf course architects enshrined in the World Golf Hall of Fame.

"Pete's list of golf courses is almost unprecedented among modern golf course architects," says Kerry Haigh, the chief championships officer for the PGA of America. "He's done courses that will be forever in memory and I'm sure down the road, just as people talk about Donald Ross and (A.W.) Tillinghast, in another 100 years we'll talk about Pete Dye in the same way."

Kohler loves to tell the story about when he expressly forbade Dye to cut down a stand of trees during the construction of Blackwolf Run and Dye ignored him, cut down the trees and staked out a green next to the stumps.

Kohler had a meeting that ran late and when he drove out to the course he saw, from a distance, smoke drifting above the tree line. Dye not only had cut down his precious trees, but he had piled them up and set them ablaze before heading home to Indiana.

An enraged Kohler called Dye, made him fly back to Wisconsin and came within inches of firing him. Dye has worked for dozens of owners and knows when it's time to sheepishly nod his head. Soon, all was forgiven.

"Mr. Kohler, he always comes up with some wild ideas," Dye says. "I never listen to him. But the deal is, his courses are successful."

Their synergy – Kohler's passion and perfectionism, Dye's eccentricity and imagination – has produced one of the best golf resorts in the world in little Kohler, Wis.

What they did at Whistling Straits boggles the mind. Kohler bought a flat-as-a-pancake former military base on the edge of Lake Michigan and told Dye to build a faithful reproduction of the classic seaside links courses in Ireland and Scotland.

Dye did it by lowering the bluff some 35-40 feet, pushing the dirt inland and bringing in more than 13,000 truckloads of sand to form a jumble of soaring dunes and jagged bunkers.

"I just moved it from A to B and it really got high and it looked OK," Dye says in his typical self-effacing style. "Got it so the gallery could see and all that stuff. And so Whistling Straits got started."

Rob Correa, executive vice president of programming for CBS Sports, loves the way the Straits presents on television.

"It's terrific," he says. "From a television perspective, we look at a golf course in three primary ways. One, what does it look like on television? Does it look spectacular? Obviously, this course checks that box.

"Secondly, are there a lot of spectators on the golf course? This course checks that box as well. The third thing is a golf course that allows for drama, players going up and down the leader board. Based on the two playoffs here (2004 and '10), it obviously checks that box as well."

An inveterate tinkerer, Dye has been back dozens of times since the Straits opened in 1998. Some of the changes he's made are minor – a green reshaped here, a bunker added or removed there – but others have been profound enough to alter the strategy for playing a hole.

"Well, it falls apart," Dye says, "and you put it back together."

Jim Richerson, the general manager and group director of golf for Kohler Co., likens Dye to a sculptor who is never quite satisfied with his work.

"He spends a lot of time shaping things, creating things, re-creating things and getting them to where he wants them to be," Richerson says. "It seems like each time he visits a site, he sees new things. He's always thinking, always tinkering, always trying to improve it, one way or another."

Dye's courses run the gamut from parkland to prairie to faux links, but one constant is that they are difficult for the average golfer and visually intimidating for even accomplished players.

"You stand on some tees or some fairways and you think, 'How on earth can I even hit the landing area or the green?'" Haigh says. "Once you have seen and played the course you find out it's playable and very fair.

"Now, some of the characteristics he puts into a golf course, some people may not like. But they certainly make you think. His courses can be intimidating and beautiful and terrifying – all at the same time."

Dye believes most golfers who complain about losing a half-dozen golf balls and failing to break 100 on his courses secretly enjoy the struggle and brag about it afterward.

"The ardent golfer," he once said, "would play Mount Everest if somebody would put a flagstick on top."

Dye was a good enough player in his youth to qualify for the U.S. Amateur five times. In 1958, he won the Indiana State Amateur and lost to an 18-year-old Nicklaus, 3 and 2, in the semifinals of the Trans-Mississippi.

But his wife, Alice, was even better – a nine-time Indiana State Amateur champion, Curtis Cup team member, winner of the U.S. Senior Women's Amateur in 1978 and '79 and captain of the 1992 U.S. Women's World Amateur team.

Alice's influence can be seen in Pete's course designs. She stressed the importance of forward tees not as an afterthought but to make his courses more enjoyable for women, juniors and seniors.

And, yes, the island green at Sawgrass was her idea.

McIlroy, who fell one shot short of joining the playoff won by Martin Kaymer at the 2010 PGA Championship, admitted he wasn't a fan of Dye's courses earlier in his career but has come to appreciate them.

"You really have to learn his courses and have your thinking hat on and be disciplined about where you position your ball," McIlroy says. "It's almost like a game of chess. You have to be on your game and be very sharp mentally.

"Honestly, I used to hate Pete Dye golf courses, but I've learned to play them and I've learned to appreciate what he tries to make you do. Sawgrass, for example, I missed the cut the first three times I played there and the last three years my performances have gotten better on that golf course.

"I think discipline is a key to playing Pete's golf courses. I've had to learn that over the years."

Dye is still very much in demand and has done the routing for what would be a fifth Kohler Co. course in the Town of Wilson, just south of Sheboygan. He doesn't hop on bulldozers much these days, but the old dirt farmer is as busy as ever.

"I've got 13 jobs going right now," he says, "and I'm behind time and over budget."

As if on cue, he politely ends the interview. He's missing Lawrence Welk.

This article was written by Gary D'Amato from Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and was legally licensed through the NewsCred publisher network.